Lion Fritsche*

“Their meetings are secret. Their members are generally unknown. The decision they reach need not be fully disclosed.”1 This statement from March 2001 exemplifies the public´s opinion about investment arbitration at that time. It might be a coincidence that in January 2001, the tribunal in the case Methanex v. United States accepted an amicus curiae or “friend of the court” submission for the first time.2 The tribunal argued that arbitration “could benefit from being perceived as more open or transparent, or conversely be harmed if seen as unduly secretive.”3 In the following years, amici interventions became a more and more common practice in investment arbitration.4

Amici are generally non-governmental organizations and other public or private institutions that consider the outcome of an investment arbitral proceeding to have a significant impact on the environment, human rights or the economy.5 Thus, amici want to raise awareness of tribunals regarding these possible impacts by filing submissions in which they express their legal or factual knowledge concerning these matters.6 In doing so, amici also enhance the legitimacy and transparency of an arbitral proceeding by giving the public an indirect voice in the arbitration.7

Despite the benefits for arbitration, such interventions come at a price. The tribunal in the Methanex case pointed out that “the acceptance of amici submissions might add significantly to the overall costs of the arbitration.”8 This process of participation and its consequences for the total costs of arbitration will be examined in the first part of the paper (B.). An increase of costs raises the question to whom the additional costs should be charged – to one or all parties or even the amicus itself? In an attempt to answer this question, it will be illustrated how tribunals ordinarily allocate costs in investment arbitration, without participation of an amicus (C.). The author will focus on the Convention on the Settlement of Investment Disputes between States and Nationals of other States (hereinafter: ICSID Convention) and its accompanying ICSID Rules for Procedure for Arbitration Proceedings (hereinafter: ICSID Arbitration Rules) as well as the UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules 2013 (hereinafter: UNCITRAL Rules).9 The paper will then address the issue of cost allocation concerning the costs incurred by amicus participation (D.), before ending in a conclusion (E.>).

A. Procedure and Impact on Costs

As a reaction to the increased participation of amici,10 ICSID amended its ICSID Arbitration Rules and UNCITRAL introduced its Rules on Transparency in Treaty-based Investor-State Arbitration (hereinafter: Transparency Rules). Rule 37(2) ICSID Arbitration Rules and Art. 4 Transparency Rules now explicitly govern the process of participation by amici.

Thereby, amici file an application in which they state their interest in the arbitration, their particular knowledge about a matter in the dispute they want to address, and their relationship to the parties. A tribunal then consults with the parties before deciding on the application. In this regard, it is important to stress that tribunals have to consult with the parties, but do not have to seek their unanimous approval. Although a tribunal would probably not decide against the expressed will of both parties,11 a unanimous will is unlikely, as the amicus usually supports the position of only one of the parties.12 If tribunals grant permission, an amicus usually files a written submission, on which the parties may respond.

A consequence of such intervention is that the duration and total costs of a proceeding increase.13 Costs are generally divided into the arbitrator fees, their expenses, the charge of an arbitral institution and the costs for the legal representation of each party.14 The logical reason for the increase is that the tribunal and the parties have to spent more time on a dispute following an amicus intervention. As the fees for the arbitrators and the legal representatives are usually calculated by an hourly rate in investment arbitration,15 these measures will inevitably lead to an increase of the total costs of arbitration.

* The author is a student assistant at the chair of Professor Dr. Stephan Lorenz at the Ludwig-Maximilian-University in Munich.

1 Depalma, New York Times (2001), Section 3 page 1.

2 Methanex v. USA,Ad-hoc Arbitration (UNCITRAL), Amicus Submission, para. 47 et seq; Nigel/Richard in: Blackaby/Richard/et al., The Backlash against Investment Arbitration (2010), p. 253, p. 259 et seq.

3 Methanex v. USA (fn. 2), para. 49.

4 Cf. Bastin, 30(1) Arbitration International (2014), p. 125, p. 142 et seq.

5 Cf. Gómez, 35(2) Fordham International Law Journal (2012), p. 510, p. 528.

6 Bastin, 1(2) Cambridge Journal of International and Comparative Law (2012), p. 208, p. 212.

7 Cf. De Brabandere in: Ruiz-Fabri, Max Planck Encyclopedia of International Procedural Law (2019), p. 12 et seq.

8 Methanex v. USA (fn. 2), para. 50.

9 These Rules are most frequently used in investment arbitration; UNCTAD Series on International Investment Policies for Development (2005), p. 5.

10 Cf. De Brabandere in: Ruiz-Fabri (fn. 7), p. 5 et. seq.

11 According to Art. V 1(d) NYC, the enforcement of an award may be refused, if the arbitral procedure was not in accordance with the agreement of the parties.

12 See infra, D.II.1, D.II.3.

13 Levine, 29(1) Berkeley Journal of International Law (2011), p. 200, p. 219.

14 Sicard-Mirabal/Derains, Introduction to Investor-State Arbitration (2018), p. 232.

15 Sachs in: Mistelis/Lew, Pervasive Problems in International Arbitration (2006), p. 103, p. 105 et seqq.

B. Cost Allocation in Investment Arbitration

As the ICSID Convention, the ICSID Arbitration Rules, the UNCITRAL Rules or the Transparency Rules do not contain any specific provision concerning the allocation of amici costs,16 it must be considered how costs are allocated in an arbitral proceeding generally.

Art. 61(2) ICSID Convention, for example, stipulates that:

In the case of arbitration proceedings the tribunal shall […] decide how and by whom those expenses, the fees and the expenses of the members of the tribunal and the charges for the use of the facilities of the Centre shall be paid.

Conversely, Art. 42(1) UNCITRAL Rules provides that:

The costs of the arbitration shall in principle be borne by the unsuccessful party or parties. However, the arbitral tribunal may apportion each of such costs between the parties if it determines that apportionment is reasonable, taking into account the circumstances of the case.

Accordingly, the allocation of costs of arbitration is mainly subject to the tribunal´s discretion, so no unified jurisprudence concerning the appropriation of costs exists.17 In the following, the author takes a more in-depth look at the approaches regarding the allocation of costs (I.). Then, how these approaches were implemented in recent decisions of ICSID and UNCITRAL tribunals is examined (II.).

I. Approaches regarding Cost Allocation

Generally, there are two ways to allocate costs between parties.

First, according to the so-called “American Rule,” each party should bear its own legal cost, whereas the costs for the arbitration itself are equally shared between the parties.18 This approach is mainly implemented in the United States and relies on the premise that the costs of arbitration are incurred while “doing business” and thus should be borne by the respective parties as part of their regular business.19

Second, the so-called “English Rule” principally requires the unsuccessful party to bear its legal costs and also the legal costs of the other party and the costs of the arbitration in full.20 For investment arbitration, the case Thunderbird v. Mexican States is occasionally considered as a turning point towards the English Rule, as the tribunal criticized the American Rule insofar that it “failed to grasp the rationale of this view.”21 It instead proposed to subject the unsuccessful party in full to the levying of costs of the arbitration.

II. Recent Practice in Investment Arbitration

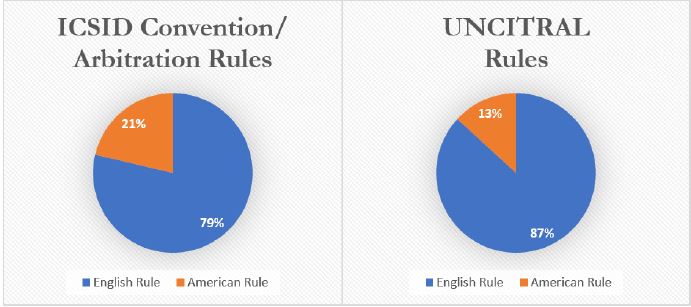

The approaches concerning cost allocation have been established, so how these approaches were implemented in recent arbitral awards will now be examined. In this regard, the author evaluated a total of 64 awards, 47 awards given under the ICSID Convention respectively the ICSID Arbitration Rules and 17 awards rendered under the UNCITRAL Rules, in a period from 2017 to September 2019.22 Awards in which tribunals shifted at least some part of the costs to the unsuccessful party, were classified as an application of the English Rule.23 Awards in which parties had to bear their legal fees respectively and the costs of the arbitration equally were classified as an application of the American Rule.

Abbildung 1: Evaluation of the recent practice

Following this evaluation, the author could observe that tribunals in principle apply the English Rule in investment arbitration.24 However, if a party is not entirely successful in jurisdiction or the merits of the case, tribunals exercise their discretion granted under Art. 61(2) ICSID Convention and Art. 42(1) UNCITRAL Rules and allocate the costs in a manner they consider equitable.25 In using this discretion, tribunals consider the relative outcome of the proceedings, the conduct of both parties during the arbitration and other relevant circumstances.26 For instance, in the case Cube v. Spain the tribunal found that if a “claim is only partly successful, it is inappropriate that the claimant should decide on the full costs of bringing the claim.”27 Thus, it ordered the respondent to bear half of the claimant´s costs, while the costs of the arbitration itself were shared equally.28

In conclusion, this evaluation shows that tribunals in principle apply the English Rule but eventually adjust it when

16 Cf. Euler, 34(2) ASA Bulletin (2016), p. 355, p. 369.

17 With further evidence: Bondar, 32 Arbitration International (2016), p. 45, p. 48.

18 Schill, 7 Journal of World Investment & Trade (2006), p. 653, p. 654 et seq.

19 Hodgson/Evans in: Baltag, ICSID Convention after 50 Years: Unsettled Issues (2016), p. 458.

20 Klein, Das Investitionsschutzrecht als völkerrechtliches Individualschutzsystem im Mehrebenensystem (2018), p. 280.

21 Thunderbird v. Mexican State, Ad-hoc Arbitration (UNCITRAL), Award, para. 214.

22 A full list of all the awards observed can be accessed under https://de.scribd.com/document/455947008/Amicus-Curiae-in-Investment-Arbitration-Legitimacy-at-Whose-Costs-Evaluation-of-Arbitral-Awards?secret_password=hsglzm9odVK1qg2GkPKy.

23 This includes seven awards, where tribunals only allocated the costs of the arbitration to the unsuccessful party while both parties had to bear their respective legal costs.

24 I.e. Teinver v. Argentine Republic, ICSID Case No. ARB/09/1, para. 258; 9REN v. Spain, ICISD Case No. ARB/15/15, para. 449; Fenosa v. Egypt, ICSID Case No. ARB/14/4, para. 13.12.

25 This is also considered as the „Relative-Success-Approach,“ Hodgson/Evans in: Baltag (fn. 19), p. 459.

26 Cf. Bondar, 32 Arbitration International(2016), p. 45, p. 52.

27 Cube v. Spain, ICSID Case No. ARB/15/20, para. 43; cf. Antaris v. Czech Republic, PCA Case No. 2014-01, para. 454 et seq.

28 Cube v. Spain (fn. 27), para. 46; cf. Silver Ltd. v. Bolivia, PCA Case No. 2013-15, para. 931 et seq.

considering the relative success of both parties.

C. Cost Allocation following Interventions in Investment Arbitration

Following the different approaches regarding cost allocation, the question is now by whom the costs incurred by amicus participation are to be borne. In this regard, there are two conceivable approaches. First, tribunals could separate the costs incurred by such intervention from the remaining costs of arbitration and impose the former entirely towards the amicus itself (I.). Second, tribunals could consider the costs incurred by amicus participation jointly with all the other costs of arbitration. Consequently, they could apply the American Rule or the English Rule concerning the entire costs of arbitration and allocate them accordingly between the arbitrating parties (II.).

I. Imposition of Costs towards the Amicus

To subject the amicus itself to the costs incurred by his participation could be justified as the “if and when” of an intervention resides within his decisional power. However, a prerequisite for such an imposition is that amici costs can be separated from the remaining costs of the arbitration at all (1.). Even if the amici costs can practically be separated, there exists no legal basis for such an imposition within the UNCITRAL Rules or the ICSID Convention (2.). Further, a cost undertaking declaration would strongly contradict the role of an amicus in investment arbitration (3.).

1. Separation of Costs in an Arbitral Proceeding

Costs in investment arbitration are generally calculated on an hourly basis,29 which makes it difficult to precisely quantify the costs of an amicus intervention alone. Nevertheless, a separation of these costs from the remaining costs does not appear to be excluded from the outset. In particular, the parties‘ submissions on costs often contain a very detailed statement of the costs incurred in the proceedings.30 Further, in the case Masdar vs. Spain, also the tribunal considered whether to separate the amici costs from the remaining costs but later decided “to assimilate those costs into the costs of the arbitration […].”31

In this respect, it seems worth mentioning that in the context of the reform of the ICSID Arbitration Rules, consideration was given to include the undertaking of the procedural costs attributable to the amicus intervention as a criterion for the admission of such interventions.32 However, such a criterion would necessarily have amounted to a separation between the costs attributable to the amicus intervention and the remaining costs of the arbitration. This shows that even the drafters of the ICSID Arbitration Rules found such a separation feasible.

Thus, a distinction between costs could practically be implemented.

2. Imposition of Costs towards the Amicus in the UNCITRAL Rules and the ICSID Convention

In order to impose the amici costs to the latter, it would have to fall under the scope of the respective provisions within the UNCITRAL Rules or the ICSID Convention.

According to Art. 42(1) UNCITRAL Rules a tribunal is only allowed to allocate the costs “between the parties [emphasis added].” Likewise, Art. 61(2) ICSID Convention also requires a tribunal to render a cost decision concerning the parties of that arbitration.33 Thus, to impose costs to the amicus, the latter would have to be a party in the sense of these provisions. This is, however, not the case. Art. 1(1) UNCITRAL Rules stipulates that if parties “have agreed that disputes between them […] shall be referred to arbitration under the [UNCITRAL Rules], then such disputes shall be settled in accordance with these Rules […].” This exemplifies that the term “party” or “parties” within the UNCITRAL Rules is a changeable term, whose definition depends on who is the Claimant and who is the Respondent in the relative dispute.34 The same holds true for the ICSID Convention, as arbitral proceedings can only be initiated by a “Contracting State or any national of a Contracting State” through sending a request “concerning the issues in dispute [emphasis added]”.35 Therefore, the term “party” or “parties” can only be defined in accordance with the underlying dispute.36 However, this dependency also means that the term “party” or “parties” can generally be defined as “disputing party” or “disputing parties.”

Thus, in order to fall under these cost-allocation-provisions, an amicus would have to be a disputing party. However, Rule 37(2) ICSID Arbitration Rules and Art. 4(1) Transparency Rules consider an amicus merely as a non-disputing party, not a party to the dispute. This distinction is appropriate, as granting a party-status in the sense of the UNCITRAL Rules or the ICSID Convention would confer the same rights and obligations on the amicus that are held by the disputing parties. This would, however, circumvent the disputing parties’ arbitration agreement, which is limited to the parties consenting to it.37

To overcome the wording of Art. 42(1) UNCITRAL Rules and Art. 61(2) ICSID Convention, one could have recourse

29 Cf. See supra, B.

30 I.e. the Submission on Costs from the Government of Canada contained a very detailed list on how many hours counsels spent on a certain matter in the arbitration (amongst other things also a submission by a non-disputing party), Windstream v. Government of Canada, PCA Case No. 2013-22, p. 18 et seq.

31 Masdar vs. Spain, Award, ICSID Case No. ARB/14/1, para. 695.

32 Proposals for the Amendments of the ICSID Rules – Working Group, Vol. 3 (2018), p. 885 et seq. – However, this proposal has been dropped in the current Working Paper – probably at the instigation of some states, according to which such assumption of costs would have been contrary to the practice under international law according to which the amicus only has to bear its own costs.

33 Cf. Rule 28 ICSID Arbitration Rules.

34 Cf. Art. 3(1) UNCITRAL Rules.

35 Cf. Art. 36(1)(2) ICSID Convention; Art. 2(2) Arbitration (Additional Facility) Rules.

36 I.e. any objection regarding the jurisdiction of the ICSID Center can only be raised by “a party to the dispute”, Art. 41 (2) ICSID Convention.

37 Cf. Methanex v. USA (fn. 2), para. 29.

to the general provisions of Art. 17(1) UNCITRAL Rules and Art. 44 ICSID Convention. According to Art. 17(1) UNCITRAL Rules the tribunal “may conduct the arbitration in such manner it considers appropriate […].” Comparably, Art. 44 ICSID Convention confers on the tribunal discretion to decide issues, but not within the ICISD Convention or the ICSID Arbitration Rules themselves.38 However, having recourse to these general rules would not only circumvent the explicit provisions on cost allocation in these rules but also reiterate that these provisions only apply to the arbitration to which only the disputing parties have agreed to.

Conclusively, the imposition of costs towards the amicus cannot be based on the provisions within the UNCITRAL Rules or the ICSID Convention as the amicus is merely a non-disputing party.

3. Legal Basis for an Imposition of Costs towards the Amicus based on a cost undertaking declaration

Alternatively, an amicus could obligate itself to bear the costs incurred by its participation by providing a cost undertaking declaration. This declaration could then serve as a legal basis for imposing costs towards the amicus. However, it cannot be assumed that an amicus would voluntarily issue such an undertaking as it also does not gain any rights or financial compensation in return.39

Rather, the cost undertaking declaration would have to be conditional to file an amici submission in a proceeding. Such a condition for participation has exceptionally40 been set out by the tribunal in the case Eiser vs. Spain, in which the European Commission wanted to intervene as an amicus.41 This form of “Buy-in-participation” would, however, immensely conflict with the amici’s role in investment arbitration. The European Commission itself pointed out that the tribunal in Eiser vs. Spain “has seriously departed from a fundamental rule of procedure by requiring the contested undertaking on costs […].”42 This is mainly for two reasons. First, it would “constitute a barrier to entry for non-disputing parties to participate in arbitration proceedings […].”43 Given the role of an amicus to support the finding of a tribunal, establishing such a barrier would be completely counterproductive.44 Second, an amicus does not only represent its interest in a proceeding, but mainly the interest of the public.45 By taking part in an arbitration, it also increases the legitimacy of the proceedings, as the public could indirectly have an impact on the tribunal´s award.46 Therefore, it would be contradictory if amici had to pay for an intervention that increases the legitimacy of the proceedings in the first place.47

Thus, since a cost undertaking declaration can only be made at the expense of the benefits of an amicus intervention, this should not be considered as a solution to the cost-allocation-problem.

II. Cost Allocation between the Parties

As the amicus at least should not be obligated to pay for its incurred costs, tribunals would have to allocate these between the parties. At this point, one could consider this paper to be concluded as the “amici costs” could be allocated between the parties together with the remaining costs of arbitration by applying either the American Rule or the English Rule. However, the author will demonstrate that neither a strict application of the American Rule (1.) nor the English Rule (2.) concerning the entire costs may provide for equitable results. To achieve such equitable results, the amici costs will once again need to be separated from the remaining costs of arbitration and allocated independently based on distinct constellations (3.).

1. Strict Application of the American Rule

When applying the American Rule, there are two reasons that call for a distinction between the amici costs and the remaining costs of arbitration.

First, the increased costs of an amicus intervention are not directly influenceable by the parties and are as such incalculable. Before filing a claim against a state, an investor must consider the chances of success and the potential risks, including the total costs of arbitration.48 As the fees of arbitrators and legal representatives in investment arbitration are generally calculated on an hourly rate,49 the amount of the total costs is challenging to assess at all, but these costs are at least expectable by the parties. Contrarily, the costs incurred by amicus participation are neither calculable nor expectable.50 Because of this incalculability, the costs incurred by amicus participation are different from the remaining costs of arbitration and should, thus, be allocated separately. In this regard, one has to bear in mind that the intervention of an amicus or even amici can decisively increase the costs of arbitration.51 Particularly, if one considers that the submission of an amicus is usually more advantageous to the position of one party, the other party would have to spend more money in order to fight the amicus intervention.52 Such a considerable increase in incalculable costs could deter an investor from filing a claim against the state if he would have to bear half of the amici costs under the American Rule,

38 Schreuer/Malintoppi, The ICSID Convention: A Commentary 2nd(2010), Art. 44 para. 53 et seq.

39 Cf. Maxwell, 3(2) Asian International Arbitration Journal (2007), p. 176, p. 181.

40 Eiser v. Spain (Amicus Curiae Submission), ICSID Case No. ARB/13/36, para. 48 et seqq.

41 The condition has been set out in the Procedural Order No. 7, which is not published. However, the Tribunal cites the relevant part of Procedural Order No. 7 in its final award, Eiser vs. Spain (Award), ICSID Case No. ARB/13/36, para. 65.

42 Eiser v. Spain (fn. 41), para. 16.

43 Eiser v. Spain (fn. 41), para. 51; cf. Report of Working Group II on the work of its fifty-seventh session (2012), para. 129.

44 Eiser v. Spain (fn. 41), para. 18.

45 Nigel/Richard in: Blackaby/Richard/et al. (fn. 2), p. 269.

46 Cf. Eiser v. Spain (fn. 41), para. 72.

47 Cf. Ruthemeyer, Der Amicus Curiae Brief im Internationalen Investitionsrecht (2014), p. 296; cf. Büstgens, Transparenz und Öffentlichkeit gemischter Schiedsverfahren (2017), p. 283 et seq.

48 Cf. Reisman/Crawford/et al., Foreign Investment Disputes: Cases, Materials and Commentary (2014), para. 167.

49 See supra, B.

50 Cf. Friedland in: Mistelis/Lew (fn. 15), p. 328.

51 Ibid.

52 I.e. Afonso states that the European Commission could not be really independent from the Member-States, 2019(34) Spain Arbitration Review, p. 113, p. 122 et seq.

irrespective of the outcome of its claim and its reliance on the amicus.53

Second, the recent practice of amici interventions exemplifies that they support the state far more often than claims of investors.54 For example, in the case Merril v. Canada, the amici explicitly submitted, “that the Investor´s claim against the Government of Canada be dismissed.”55 This is expected because amici usually represent the same public interests as the state. Therefore, the strict application of the American Rule would in most cases require the investor to bear costs of an amicus participation, which is knowingly not in his favor.

In light of this, a strict application of the American Rule would not always ensure equitable results, which requires the distinction of amici costs from the remaining costs of arbitration.

2. Strict Application of the English Rule

Alternatively, tribunals could strictly apply the English Rule when allocating the entire costs of arbitration. However, there are three reasons why also the application of the English Rule could lead to inequitable results, necessitating a distinction of the amici costs from the remaining costs of arbitration.

First, amicus participation can be fruitful for the entire dispute, or for at least one party,56 but it does not necessarily have to be. In general, it is difficult to establish whether the submission of an amicus had any influence on the decision of a tribunal.57 One of the very few exceptions to this observation is the case Biwater v. Tanzania, in which the tribunal explicitly found the amicus submission to be “useful.”58 However, there might be cases in which the claim of an investor or the defense of a state is already evidently without merit. The additional support of an amicus would – from the perspective of the prevailing party – not even be necessary for a favorable final decision and would only increase the costs of arbitration. In this case, it is questionable whether the unsuccessful party, which bears the remaining costs of arbitration under the English Rule, should, in addition, be strained by the non-essential costs of the amicus participation.

Second, shifting the entire costs to the unsuccessful party, could incentivize either party to collaborate with amici to improve their standing in arbitration at the cost of the counterparty.59 This collaboration could lead not only to an inadmissible reimbursement of the amicus,60 but also entirely contradict the role of the amicus to enhance the legitimacy of an arbitral proceeding.61

Third, both parties before arbitration mutually benefited from the investments based on the underlying investment treaty.62 An investor would, however, only make investments in another country, if these investments are sufficiently protected by the investment treaty and, most importantly by the state’s erga omnes offer to arbitrate.63 Thus, the arbitration clause as such is one of the most decisive prerequisites for both parties to consequentially profit from an investment. Insofar, both parties depend on the legal existence and the public acceptance of such a clause to some extent. As the intervention of an amicus enhances the transparency and the legitimacy of an arbitral proceeding,64 it is arguable to allocate the costs incurred by such participation equally between the mutually benefiting parties under the American Rule.65 Contrarily, the strict application of the English Rule would shift the price for this benefit exclusively to the unsuccessful party.

Hence, the mere application of the English Rule concerning the entire costs could not always ensure equitable results either, necessitating a distinction between the amici costs and the remaining costs of arbitration.

3. Distinct Constellations instead of General Application

Considering that neither the American Rule nor the English Rule can consistently allocate the costs following an amicus participation equitably, it seems appropriate to examine the allocation of these costs separately through varying constellations.

In doing so, the author proposes that tribunals must establish a balance between the incalculable costs incurred by an amicus intervention, the states’ sovereignty over its national law, the support of the amicus for one of the parties and the subsequent increase of legitimacy regarding the arbitral proceeding from which both parties mutually benefit.

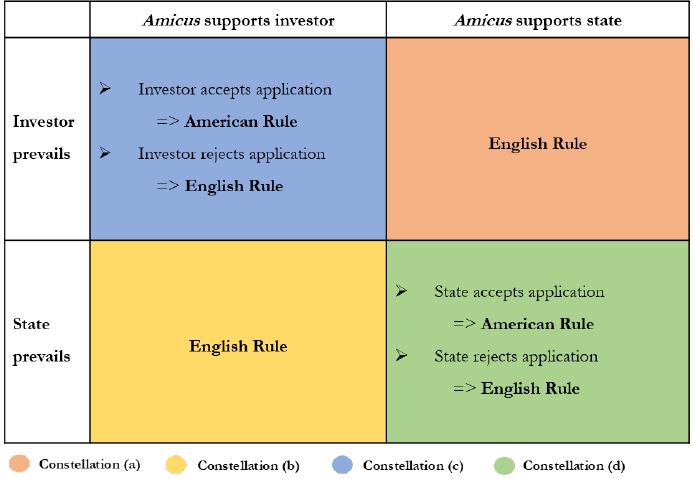

For this purpose, it is helpful to distinguish between the following constellations concerning the intervention of an amicus and the outcome of an arbitral proceeding. Thereby, “support” means that an amicus substantially agrees with the position of one of the parties.

Investor prevails while amicus supports the state (a)

State prevails while amicus supports the investor (b)

Investor prevails while amicus supports the investor (c)

State prevails while amicus supports the state (d)

Such a clear assignment to a party is of course not always possible.66 In most cases, however, it can be derived from the

53 Cf. Schill (fn. 18), p. 674; Cf. Riesenberg, 60 Duke Law Journal (2011), p. 977, p. 1009 et seq.

54 Bastin (fn. 4), p. 135.

55 Merril v. Canada (Amicus Submission), ICSID Case No. UNCT/07/1, para. 59.

56 See supra, D.II.1.

57 Brabandere in: Ruiz-Fabri (fn. 7), p. 12.

58 Biwater v. Tanzania, ICSID Case No. ARB/05/22, para. 359.

59 Cf. Segger, Der Amicus Curiae im Internationalen Wirtschaftsrecht (2017), p. 471.

60 I.e. Koua Poirrez v. France (ECHR), Application No. 40892/98, para. 68 et seq.

61 See supra, A.

62 Büstgens (fn. 48), p. 300.

63 McLachlan in: Van den Berg, 50 Years of the New York Convention: ICCA International Arbitration Conference(2009), p. 95, p. 97; Sicard-Mirabal/Derains (fn. 14), p. 42.

64 See supra, A.

65 Cf. Büstgens (fn. 48), p. 300.

66 The United States occasionally interpret their free trade agreements without supporting either of the parties, Railroad Dev. v. Guatemala (Amicus Submission), ICSID Case No. ARB/07/23, p. 1.

amicus submission which of the parties the latter supports.67

Subsequently, the author exemplifies two possible exceptions to these constellations (e). This will be followed by an explanation on how these constellations comply with the application of the American Rule or the English Rule concerning the entire costs of arbitration (f). In this regard, it is essential to mention that the author does not want to generally privilege either the investor or the state. Instead, the author tries to propose an equitable solution following the demand on a tribunal to not “unduly burden or unfairly prejudice either party” under Rule 37(2) ICSID Arbitration Rules and Art. 4(5) Transparency Rules.

a) Investor prevails while amicus supports the state

In this constellation, the application of the English Rule would be equitable.

First, the slight imbalance in favor of the state could be diminished. This is because in most cases the state allegedly violated the investment treaty by exercising its sovereignty over the national law. Thus, it is the state that established the incentive for an investor to claim its rights under the investment treaty and thereby created the possibility for an amicus to participate in such arbitral proceeding. The investor, who trusted in the legality of its long-term investment, has to take the risk of claiming damages under the investment treaty. Because of this risk, the investor should be relieved from the incalculable costs in case his claim is successful.

Second, there is no possibility for a collaboration between the investor and the amicus, which would necessitate a deviation from the English Rule. In such a case of collaboration, an investor could convince an amicus or even amici to file submissions to support his or her claim and thereby persuade the tribunal of its merit. In return, the investor could offer to redeem the amicus from its costs.68 However, in this constellation the amicus explicitly supports the position of the state, which extinguishes the possibility of collaboration.

Therefore, the English Rule would ensure an equitable result in this constellation.

b) State prevails while amicus supports the investor

In cases where the state prevails and the amicus supports the investor, the strict application of the English Rule would likewise lead to an equitable result because there is no such tendency in favor of the state that needs to be balanced by a tribunal. Rather, the investor is the unsuccessful party to an arbitral proceeding, although his claim was additionally supported by an amicus submission. Despite this supportive intervention, the tribunal still found the claim to have no merit in the end. Thus, the groundlessness of the investor´s claim becomes even more apparent. In such instance, the investor is not worthy of being protected by a different allocation of the amici costs. To the contrary, it would be equitable to shift these increased costs to the investor in full, who first established the possibility for amicus participation in an arbitral proceeding by filing its meritless claim. Therefore, tribunals should apply the English Rule in this constellation.

c) Investor prevails while amicus supports the investor

The allocation of costs is more intricate in cases where the investor prevails over the state while also being supported by an amicus intervention. On the one hand, tribunals could once more apply the English Rule, as the investor is still unilaterally exposed to the sovereignty of the state.69 Further, it is also possible to understand the increased costs as part of the damages an investor claims following a violation of the investment treaty by the state.70

On the other hand, applying the English Rule in this constellation could indeed lead to a collaboration between the investor and the amicus.71 However, an indirect redemption of the amicus would not only violate the principle of good faith but also be incompatible with the fact that amici are not entitled to claim reimbursement form the parties.72 To prevent such collaboration from the outset, tribunals could exercise the American Rule by splitting these costs equally between the parties.

In light of this divergence, the author proposes the following distinction. According to Rule 37(2) ICISD Arbitration Rules and Art. 4(1) Transparency Rules tribunals must consult with the parties over an amicus application: If an investor rejects such application, as he considers its claim to have merit anyway, the tribunal should apply the English Rule under the arguments mentioned above and allocate the costs incurred by amicus intervention to the unsuccessful state. However, if an investor consents to an amicus application, tribunals should apply the American Rule, as there is at least a possibility of collaboration with the amicus. This solution grants a confident investor the option to forego the support of an amicus in order to avoid the costs associated herewith but also ensures that the investor cannot persuade the amicus to intervene at the exclusive cost of the unsuccessful state.

d) State prevails while amicus supports the state

In case the state prevails over the investor while also being supported by an amicus submission, one could argue that the support of the amicus would put the state in an even more favorable position, which would justify an application of the American Rule. The reason being that the investor generally has a right to pursue any possible violations of the investment treaty by bringing a claim to arbitration, despite being ultimately unsuccessful. In case of such a claim, a tribunal might decide a proceeding in favor of the

67 I.e.: Merril v. Canada (Amicus Submission), ICSID Case No. UNCT/07/1, para. 59; Pac Rim v. El Salvador (Amicus Submission), ICSID Case No. ARB/09/12, p. 2; Lilly v. Canada (Amicus Submission), ICSID Case No. UNCT/14/2, p. 1; Bear Creek v. Peru (Amicus Submission), ICSID Case No. ARB/14/21, p. 17.

68 Cf. Segger (fn. 60), p. 471.

69 See supra, D.II.3.(a).

70 Rowe, 31 Duke Law Journal (1982), p. 651, p. 657; Wena v. Egypt, ICSID Case No. ARB/98/4, para. 130.

71 See supra, D.II.2.

72 See supra, D.II.2.

state, because an amicus submission made it aware of the severe impacts the investments have on the public good of that country. For example, in the case Lilly v. Canada, one amicus argued that the alleged violation of the state would at least be justified by the “future economic prosperity across Canada’s business sectors.”73 If a tribunal, being aware of this public interest, now decides against the investor,74 it would be equitable to share at a minimum the amici costs that originally raised this issue of public interest.

Furthermore, both parties profited from the investments before arbitration. Thus, it seems generally legitimate to allocate the costs for representation of the public interest regarding this profit equally between the parties.75 Moreover, there is the same possibility of a collaboration between the state and the amicus, which could incentivize the latter to file a submission in favor of the state and thereby profit.76 Insofar, one could argue the application of the American Rule to be equitable.

To the contrary, one could argue that a state should not pay for the unfoundedness of an investor´s claim if an amicus considers the alleged violation of the investment treaty by the state to be in the public interest. The reason being that the interest of the public would outweigh the investor´s monetary interest justifying the shift of the amici costs to the investor by applying the English Rule.

In light of this, the author proposes once again a distinction based on the consultation according to Rule 37(2) ICISD Arbitration Rules and Art. 4(1) Transparency Rules: If the state rejects the application of an amicus, as it considers its defense to be successful anyway, tribunals should apply the English Rule concerning the amici costs. However, if the state consents to such an application, tribunals should apply the American Rule by considering its mutual benefit for both parties and the slight imbalance at the expenses of the investor.

e) Possible exceptions to the preceding constellations

Despite these established equilibriums, the author points out two situations as examples, in which tribunals might legitimately deviate from these constellations.

First, there could be cases in which an amicus tries to abuse the proceedings by filing multiple submissions without any merit.77 In such case, tribunals should apply the American Rule, as neither party profited from such amicus intervention.

Second, tribunals should deviate in cases with a financially strong investor – for example ranked in the Fortune´s Global 500 – who claims damages from a developing country.78 First, the argument of incalculable costs incurred by amicus intervention and the investors’ risk in pursuing its rights under the investment treaty is no longer valid,79 as the investor can resort to much higher financial resources than the state. Second, a state could still exercise its sovereignty by changing its national law at the expenses of the investor. However, before making such change it would have to be weighed against any financial aid this state receives from the investor.

Thus, tribunals might, especially in constellations (a) and (c), deviate from applying the English Rule in favor of the investor and allocate the amici costs under the American Rule.

f) Constellations in the context of the remaining costs of arbitration

In conclusion, the author comes to the following results concerning the allocation of amici costs exclusively.

Abbildung 2: Summary of the four constellations

These proposals are in line with either the application of the American Rule or the English Rule regarding the remaining costs of arbitration. On the one hand, if a tribunal wants to apply the American Rule in general, constellations (a) and (b) would deviate from such an approach. However, this deviation could be justified if one compares the amicus to a witness of the unsuccessful party. The costs incurred by the participation of that witness/amicus are, in principle, to be borne by that party, as part of their legal costs.80 By making each party bear its costs for legal representation under the American Rule, the unsuccessful party could still pay for the amici costs in full. Only where either the investor or the state rejects the application by an amicus, tribunals would have to exercise their discretion as described in constellations (c) and (d).

On the other hand, if a tribunal wants to apply the English Rule concerning the remaining costs of arbitration, constellations (c) and (d) could deviate from such an approach if

73 Lilly v. Canada (fn. 69), p. 13.

74 In Lilly v. Canada (Award), the tribunal dismissed the investor´s claims in its entirety, ICISD Case No. UNCT/14/2, para. 480.

75 See supra, D.II.2.

76 See supra, D.II.2., D.II.3.(c).

77 Cf. Lamb/Harrison/et al., V(2) Indian Journal of Arbitration Law (2016), p. 72, p. 88.

78 According to a study conducted in 2007, 20 percent of all investors were companies ranked in the Fortune´s Global 500, Anderson/Grusky, Challenging Corporate Investor Rule (2007), p. 5.

79 See supra, D.II.3.(a)

80 Cf. Lew/Mistelis/et al., Comparative International Commercial Arbitration (2003), p. 573; cf. Waincymer, Procedure and Evidence in International Arbitration (2012), p. 976.

the prevailing party consents to the amici intervention. This deviation is legitimate, as tribunals often apply the English Rule in principle while making adjustments to that apportionment based on the relative success of both parties.81 By exercising this discretion, tribunals could award half of the costs incurred by amicus participation to the successful party, which would have to be borne by the latter under the American Rule.

These deviations, however, also make clear that the costs incurred by amicus participation have to be calculated separately from the remaining costs of arbitration to establish an equilibrium between the benefits of amici interventions and the disadvantages for the parties resulting thereof.

D. Conclusion

It follows from these constellations alone that the allocation of costs incurred by amicus participation is complicated. In order to get a grip on this cost-allocation-problem, tribunals should distinguish the amici costs from the remaining costs of arbitration, as only such a distinction can ensure equitable results. When allocating these costs, tribunals should determine the conflicting interests between the investor and the state, and balance them in a manner following the constellations mentioned above.

In general, a profound way to diminish the cost burden for the parties would be the restriction of the number of pages and matters to be addressed by an amicus.82 In any case, parties should encourage the participation of amici as they increase the legitimacy of an arbitral proceeding, from which both parties mutually benefit. Considering the downfall of investment arbitration in the EU following the “Achmea decision” of the ECJ,83 such increased legitimacy could secure the future of the investment arbitration mechanism.84 Thus, amici should not only be considered as a “friend of the court” but also as a “friend of the parties.”

81 See supra, C.II.

82 Dimsey in: Euler/Gehring/et al., Transparency in International Investment Arbitration, A Guide to the UNCITRAL Rules on Transparency in Treaty-Based Investor-State Arbitration (2015), p. 191.

83 Fritsche, Nr. 1 StudZR-WissON (2019), p. 63, p. 65 et. seq.

84 Cf. Butler, 66 Netherlands International Law Review (2019), p. 143, p. 176.